Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

DH and Media Studies Crossovers Vol. 3(3)

Andrew deWaard

University of California, Los Angeles

DH + CMS

The fields of Digital Humanities and Cinema & Media Studies are an increasingly fruitful pairing. Rather than traditional publication, DH tends to treat “the project as basic unit” and these “projects are both nouns and verbs” (Burdick et al. 124), so we can point to the many proliferating, continuing projects in DH-CMS as proof of that healthy partnership: Project Arclight, Kinomatics, Cinemetrics, MediaCommons, Vectors, Scalar, Audio-visual Cinematic Toolkit for Interaction, Organization, and Navigation, Visualizing Vertov, [in]Transition, ScripThreads, Bookworm, Culturegraphy, and more. At UCLA, we’re hoping to add ClipNotes to that list.

Before demonstrating how our software program works and the opportunities it creates for teaching, I’d like to briefly comment on a significant way Cinema and Media Studies differs from many of the fields that do DH work: our “data” are not only under copyright, but under strict copyright by an industry that is highly litigious and actively monitors copyrighted material online. Because our cultural material is often film and television, Hollywood or otherwise, Cinema and Media Studies scholars face certain restrictions in how we can pursue the kind of open, collaborative, data-driven research advocated by the Digital Humanities. As Burdick et al. explain in Digital_Humanities: “digital approaches are conspicuously collaborative and generative, even as they remain grounded in the traditions of humanistic inquiry” (3). The conspicuous element of that equation is often more difficult in CMS. Tight copyright control may in fact be one of the reasons Cinema and Media Studies has been comparatively slow to adopt digital methods, along with the fact that sound and image are inherently more difficult to catalogue and quantify than the written word. ClipNotes is an attempt to mitigate both of these thorny issues.

There are a wide variety of video annotation platforms under development (which we catalogue on our resources page), such as Mediathread, SocialBook, EVIA Digital Archive Project, Open Video Annotation, VideoANT, Anvil, and Domeo. These platforms all differ from ClipNotes in some essential way: they are either purely web-based, requiring you to upload video files, making them untenable for full-length copyrighted material, or they are designed with a vast, complex metadata schema for wide-ranging fields and applications, making them unappealing for our project’s specific goal of increasing usage of annotation and digital humanities methods in the field of Cinema and Media Studies. ClipNotes is purposefully simple and easy-to-use, yet powerful in its possibilities.

How ClipNotes Works

ClipNotes is an open-data instructional software project which facilitates video annotation and opens up teaching opportunities utilizing collaboration and student knowledge production, detailed below. The software was first programmed by Dr. Stephen Mamber in 2012 and is under continuous development by Steve and a team of graduate students in the Cinema and Media Studies program at UCLA.

For obvious copyright reasons, ClipNotes.org does not host films; users must personally encode a video file from a DVD or other source (see instruction page: Creating the Video File). Once the video is ready, the user can then utilize the ClipNotes toolkit, which includes three main features:

- an XML[1] schema[2] for metadata[3]-rich data files that markup[4] film and video (detailed below). This process of marking-up video emphasizes the continuing importance of deep, textual analysis, but also opens up possibilities for new knowledge production by sharing structured data.

- a searchable, public, user-submitted database of XML files that can be used for research and instructional purposes.

- a laptop/mobile app (iOS, Windows) that can use these XML files to facilitate the presentation of films in a segmented, non-linear, granular fashion that expands the possibilities of both textual, cinematic analysis as well as formal and thematic instruction.

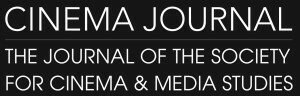

There are just 3 elements to the interface of the ClipNotes app as well:

- the video with playback controls

- the text annotation

- the quickly-accessible, scrollable menu

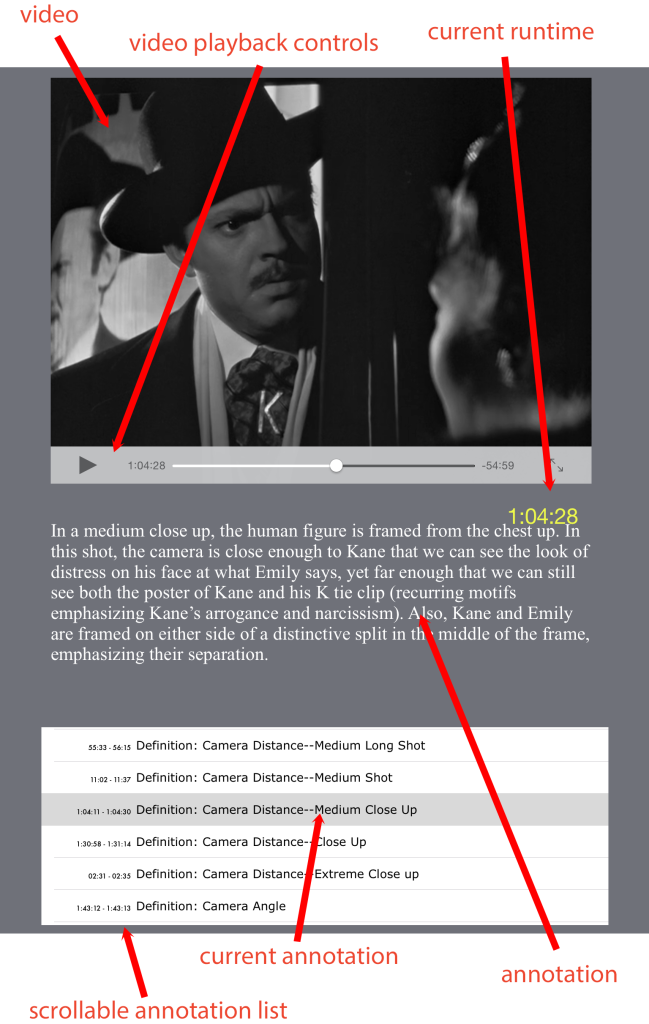

The backend to this visual interface is an XML file that organizes the annotations; it also requires three elements for each clip annotation:

- timecodes tagged with <Start> and <End>

- clip annotations tagged with <Description>

- clip titles, which appear in the menu, tagged with <Caption>

This XML file is produced separately from the app, either in a basic text editor or an XML editor (see our instruction page: Creating the XML File). We could have allowed this tagging and annotation to be created within the app, but decided it was important for the user to work with the “raw data” of segmentation in order to think differently about moving image analysis. What does it mean to “edit” a film or television through markup and segmentation? How do we enter into dialogue with the text through annotation? Does moving back and forth in a non-linear manner through a text change our experience of it? What new insights can be gained through discrete, granular analysis of only certain portions of a moving image text? How might this “data” generated through segmentation and metadata be used in other ways such as distant reading and cultural analytics?

One of the tensions the ClipNotes team struggles with is simplicity versus complexity in metadata. To a user familiar with the Text Encoding Initiative, it would appear we have clearly sided with simplicity. To many cinema and media studies scholars, however, this is potentially complex, as coding and markup language are not a common part of our traditional methodology. But we are also hoping to reach an audience beyond scholars. We want undergraduate students to be able to learn how to annotate with ClipNotes and XML as a course assignment, and we hope that ClipNotes might appeal to the casual cinephile as well, adding their non-academic insights to the public database. We do plan to develop an optional, more detailed schema for film-focused categories and tags of analysis, and we hope to adhere to community standards such as the W3C Open Annotation Coalition, though again, we hesitate to add too much complexity so as to maintain the tool’s ease of use.

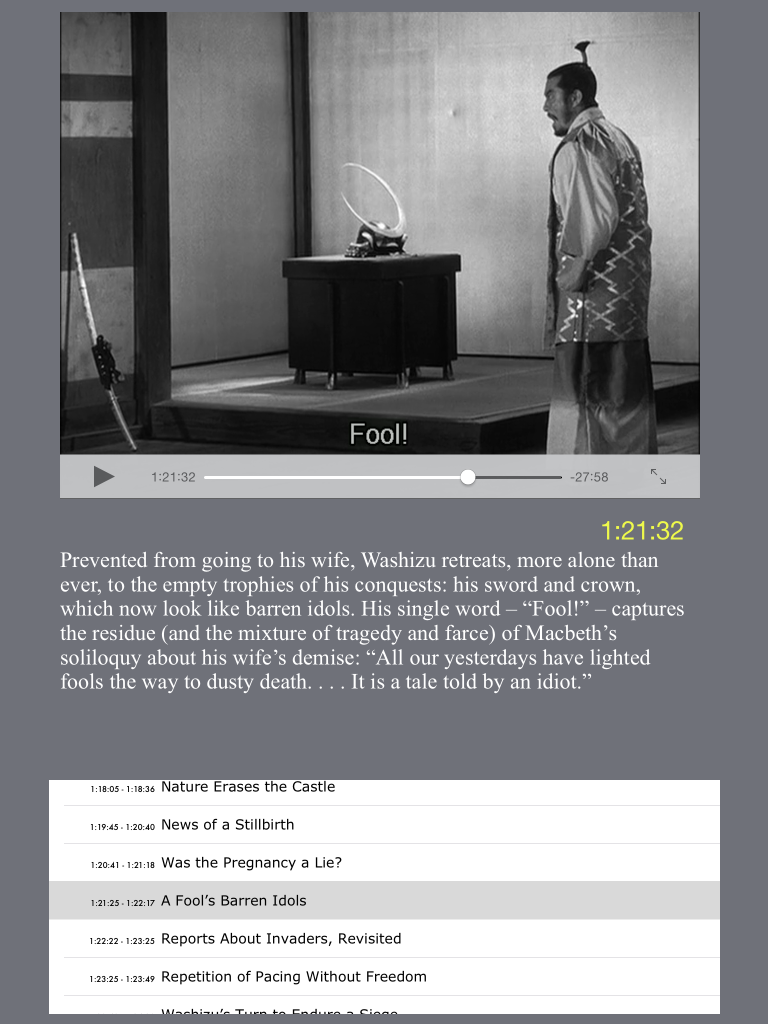

Open-Access Database of Annotation Files

A preliminary public repository of XML files is now available at ClipNotes.org, which users are encouraged to download from and submit to. We currently have a little over 60 films annotated, the majority of which trace recurring stylistic and thematic patterns throughout a film, and 10 files which were designed for instructional purposes, detailed below. With further development, we hope this database will become an increasingly useful teaching resource for instructors, as well as a place for scholars to share their analytical research, a practice that barely exists in the field of cinema and media studies. As an example, Dr. Robert N. Watson, English professor at UCLA, recently published a BFI Film Classics book on Throne of Blood and he has produced an annotation XML file that exhaustively catalogues the film with regards to its adaptation of Macbeth. You can watch the film while reading his annotations, which include comparing the original text from Shakespeare’s play to how Kurosawa has adapted it in an audiovisual medium. We’re thrilled to have this file as a very high quality example of annotation in ClipNotes that also functions as a media supplement to his book.

Fig. 3: Kurosawa’s adaptation of Macbeth in Throne of Blood is catalogued in this annotation file created by Robert N. Watson that accompanies his BFI Film Classics book

By separating the annotation file from the video file but maintaining a central, public database of XML files, ClipNotes can facilitate collaborative work without needing to host the copyrighted text. The video file is encoded by the user, thus avoiding any hosting of copyrighted material, but the app connects the video to an XML file, either personally written or downloaded from the online database. The UCLA library’s intellectual property lawyers are confident that ClipNotes is a fair interpretation of educational fair use and that library iPads containing encoded DVDs are acceptable as long as the original films are already available in the library. This leads us to believe that the split-file approach we have employed is a good workaround for the challenge of collaborating on copyrighted moving image material.

Teaching with ClipNotes

In addition to assisting annotation, research, and presentation, ClipNotes facilitates unique pedagogical opportunities as well. At UCLA, we integrated ClipNotes into a first-year History of American Film course, partnering with a campus library who provided customized iPads with ClipNotes to all of the teaching assistants, who were then able to collaboratively standardize instructional material among their many discussion sections. Using ten of the films screened in class, TAs developed annotated instructional material for core issues they wished to demonstrate in their discussion sections: narrative construction; cinematography; sound; editing; mise-en-scene; stylistic-thematic analysis; interpretation and meaning; gender, race and representation; and genre.

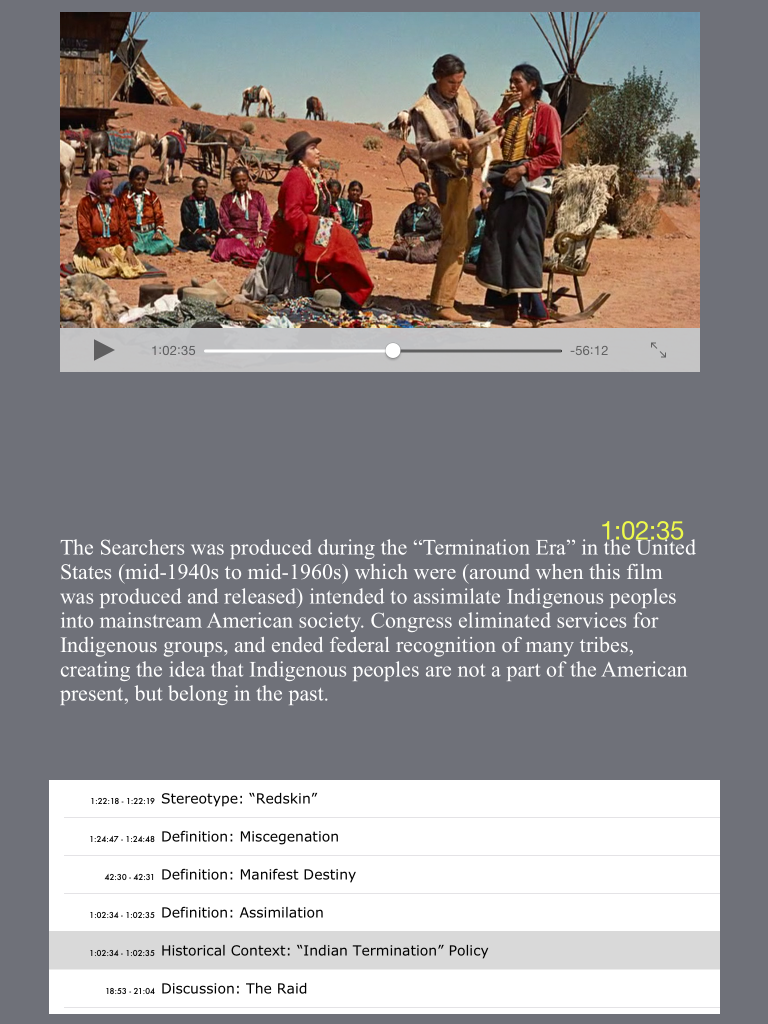

Fig. 4: The implications of race and representation are introduced in this annotation file for The Searchers

In class, TAs were more able to teach quickly and efficiently the fundamentals of film form, style, and interpretation, difficult topics to teach because of its many, diverse incarnations. The library also made a number of iPads available to students in the library to access on their own time, and though we expected only minimal use, the students made ample use of this opportunity to review terminology and clip examples for their assignments and final exam. This pilot project generated a wealth of positive feedback and we are now in the process of expanding our collection of annotated films in preparation for more classes across campus and at partner universities (please contact us if you would like to be involved or just want more information).

The Citizen Kane file, seen in the above interface image, is an example of an instructional usage of ClipNotes, teaching the terminology of cinematography through quick and comprehensive access to Citizen Kane’s landmark visual style. Salient examples of deep focus, deep space, triangular compositions, door and window framings, and graphic matches are all catalogued, as are the visual motifs of light and shadow, bars and fences, and mirrors. The ability to quickly but briefly demonstrate a series of scenes is a tremendous resource in a lecture or presentation situation, particularly non-static examples, such as sound or camera and character movement. One of the distinct strengths of film as a medium is the symphonic arrangement of audiovisual patterns over the course of the text, something that is lost in merely showing screen grabs or a few extended scenes.

Another teaching opportunity with ClipNotes arises with the possibility of teaching students how to make their own annotation files, either individually or as a collaborative assignment. Graduate level classes at UCLA have been implementing this assignment for a few years already, which is where many of the XML files in our database originate. By requiring students to markup their film analysis into an XML file that will be made available online, students are encouraged to think of their work as knowledge production that might prove beneficial to others. Not only do students improve their skill in granular film analysis, but they learn the responsibilities of knowledge production and the opportunities of open-access resources. In addition, students become an essential part of the long term effort to generate large data sets of audiovisual analysis and metadata, opening up potential quantification and data-mining possibilities in the future.

“When working with the flexible form of the database,” Tara McPherson writes in one of the first explicit engagements with media studies and digital humanities, “scholars reimagine connections between research and analysis that are not necessarily based on the structure of a linear argument, but may be multiple, associative, digressive, even contradictory” (121-122). ClipNotes is designed with these possibilities in mind, that the collaborative generation of a public database of film and television annotations might allow future scholars to study different and larger cultural dynamics than traditional analysis has allowed. Though the app itself specializes in solitary texts, discovering and annotating micro-relationships, the larger database project has the potential to produce broad, macro-cultural insights into film and television as a result of this wide-ranging data. The Cinemetrics project has demonstrated how data about just a single metric (shot-length) can produce rich, historical insights; imagine Cinema and Media Studies scholars had robust data on tracking shots, musical cues, western iconography, plot structures, dialogue duration by gender, and any other metric across a wide database of film and video? This structured data is not that far out of reach, but it would need to be produced by close analysis and annotation, in an open-format such as XML, by a dedicated community committed to iteration and interoperability. The ClipNotes project is proposing just one of many possible visions for how this process might develop, and we hope our app and classroom applications might provide an incentive to consider integrating such an open-data mentality to teaching and researching in Cinema and Media Studies.

Please visit ClipNotes.org for more information.

Works Cited

McPherson, Tara. “Introduction: Media Studies and the Digital Humanities,” Cinema Journal 48, no. 2 (Winter 2009).

Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp. 2012. Digital_Humanities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[1] XML: eXtensible Markup Language (XML) is a basic method of describing and structuring data through elements, defined by tags. For ClipNotes, we tag timecodes, annotations, and titles for each clip.

[2] Schema: Because XML has no predefined tags, but are instead chosen by the author/community, an XML schema is an agreed upon set rules for how to define the structure and content of XML documents. ClipNotes currently uses a very basic set of tags, barely qualifying as a schema, but our intention is to develop a richer structure in the future.

[3] Metadata: In short, data about data. Metadata gives information about other data, such as describing how it is formatted and how/when/by whom it was collected. ClipNotes aims to generate metadata about moving image clips, such as timecodes, annotations, and titles.

[4] Markup: Deriving from the revision process of manuscripts, where editors “marked up” paper, a markup language is a system of instructions for the software to carry out certain actions. ClipNotes users must markup video in XML format so that the app can segment and annotate the video clips.