JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (2) Revisiting the Film History Survey Marcos P. Centeno Martin, Birkbeck, University of London

JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (2) Revisiting the Film History Survey Marcos P. Centeno Martin, Birkbeck, University of London

Film history surveys have traditionally revolved around North American and European developments. However, the digital era allows an increasing access to film cultures from other regions, which is forcing the redefinition of film history surveys and their learning methodologies. Educators in the twenty-first century now have a responsibility to update their approaches to the discipline by challenging its traditional Euro-American focus. Nevertheless, that is not an easy task, as film studies has evolved from Western canons, paradigms, and models which are unsuitable for the study of ‘other’ cinemas.

Latin-American filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino noticed the need to defy dominant modes of representation in their 1969 manifesto Hacia un tercer cine (Towards a Third Cinema). Scholars followed suit, but mainly in Asia, where they started to trace clearer evidence of alternative film cultures. During the following decade, they identified Japanese cinema as the first example of an ‘other’ national cinema, with scholars such as Noël Burch categorically defending the uniqueness of Japanese cinema, given its stylistic, financial, and technical autonomy from the West. However, how can we interrogate this cinema if we only use the theoretical keys available in the West? Film history surveys need to introduce concepts and ideas developed in distant philosophical and artistic traditions. This methodology should enhance students’ understanding of how Japanese cinema in particular seems to have resisted the institutional Hollywood mode of representation, not so much as an act of opposition but rather of indifference.

A closer look at the local cultural context should, however, not forget the transnational dimension of cinema and add questions challenging essentialist approaches to Japanese cinema that have been articulated from a Western perspective and have traditionally regarded this film culture as isolated from the rest of the world. This was the weak point of Burch’s earliest introduction to Japanese cinema, which resulted from its “discovery” in the West following the success of Akira Kurosawa´s Rashōmon, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 and an Academy Honorary Award in 1952. This work initiated the burst of Japanese films into European film festivals in the 1950s, with Kenji Mizoguchi leading the wave with The Life of Oharu (Saikaku ichidai onna, 1952), which won the Golden Lion, followed by Ugetsu monogatari (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshō dayū, 1954), which won Silver Lions. Subsequent film history surveys have often included Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi as embodiments of national film identity in terms of cinematographic styles, while scholarly takes on Yasujirō Ozu, such as Donald Richie’s Ozu: His Life and Films, isolate stylistic traits to define Ozu as the most Japanese of the Japanese directors.1

For all the emphasis on the distinctively Japanese qualities of the filmmakers’ works, film history surveys must avoid essentialist approaches and acknowledge the complexities of transnational influences. For instance, Kurosawa´s most remarkable works were deeply influenced by the philosophical and moral conflicts depicted in Western literature, including William Shakespeare’s King Lear, adapted in Ran (1985), and Macbeth in Throne of Blood (1957); as well as Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych, which inspired Ikiru (1952). The impact of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Humiliated and Insulted can be seen in Red Beard (Akahige, 1965) and Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai, 1954) is a direct reference to the classical Greek tragedy Seven against Thebes by Aeschylus.

Ozu and Mizoguchi’s unique styles can be used to explain Japanese Classicism (in David Desser’s sense of classicism, itself inspired by Audie Bock’s taxonomies), a distinctive paradigm in Japan’s film history, by paying attention to the cinematic traits derived from Japanese artistic traditions.2 However, film history surveys should also introduce Ozu and Mizoguchi’s works by interrogating their transnational aspect, as they began their careers in the 1920s as filmmakers seeking to modernise cinema by adapting Western models, such as using actresses as opposed to the Kabuki theatrical tradition, where men played the female roles. In addition, they rejected the tradition of benshi narration, opting instead for the Western practice of intertitles in order to prevent narrators from modifying the meaning of their works through their interpretations. This tendency was reinforced after the 1923 Kanto earthquake, when damage to Tokyo studios greatly reduced domestic production. The shortage of Japanese films triggered an influx from abroad, particularly German films by Fritz Lang, Friedrich Murnau, and Ernst Lubitsch, and American films directed by Howard Hawks, Josef von Sternberg, and Erich von Stroheim, all of whom had a great impact that deserves to be carefully assessed.

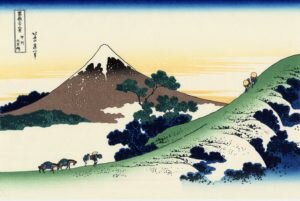

Only once the transnational aspect of these ‘early masters’ is properly framed are students ready to understand the nuances of their singularity by assessing how the aforementioned filmmakers did not merely imitate the West but renewed film language, combining elements from the West and from their own cultural background. For example, in Seven Samurai, Kurosawa used his mastery of Hollywood cinematic techniques to reinvent the pre-war chambara, or samurai film. He did so while maintaining elements such as tateyaku (strong and smart warriors) and nimaime (weak but handsome and kind-hearted secondary characters), roles which can be found in Kabuki theater.3 Additionally, Ozu’s empty shots and passage of time can be associated with the representation of “emptiness” (mu) in Japanese traditional painting, the fleeting world in ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and the sensitivity to the ephemeral (mono no aware) in Japanese poetry. Mizoguchi’s cuts and decentered framing echo the philosophical concept of kire (cut) in Japanese.4

As a consequence, new methodologies need to incorporate these epistemological keys developed in distant contexts. On the other hand, they also need to interrogate Western terms in relation to the cultural context in which there are implemented. For example, Ozu’s empty shots and Mizoguchi’s long takes, which epitomise Japanese classicism, are a blatant distortion of Classical Hollywood Cinema. They were considered modernist traits in the West and inspired the European renewal of the cinematic language from the 1960s.5 Similarly, Yasuzō Masumura’s fast editing in Kisses (Kuchizuki, 1957) and Susumu Hani’s extreme close-ups in his Children Who Draw (E o kaku kodomotachi, 1956) were deemed modernist traits, while they actually owe more to Hollywood habits.6

A transnational methodological approach should also pay attention to the battery of film language elements that followed different developments throughout history. As an example of this, Kenji Iwamoto notes that the English term “close up” is a cultural expression not equivalent to the Japanese translation ōutsushi.7 While in the West, “close up” connotes closeness and an intimate approach to the scene, in Japan it implied an enlargement. In Western cinema, close ups had been used “as a window to the spirit or human heart.”8 Learning this, students may better comprehend the traits of Ozu and Mizoguchi´s classicism, which were characterised by the opposite strategy: highlighting the most dramatic moments through wide shots. Students can see how and why, in fact, one of the singularities of the classical Japanese cinema was the relative absence of close ups.

Kōshū inume-tōge (“Inume Pass, Kōshū”, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, no. 41, Katsushika Hokusai, 1830). Image from Visipix.com.

The Life of Oharu (Saikaku Ichidai Onna, Kenji Mizoguchi, 1952). Screenshot taken by author.

To design these film history surveys, it would be helpful for educators to add readings providing an introduction to the links between films and the cultural tradition in which they are made. For example, Iwamoto explains that while close ups were rooted to Western patterns of representation, from painting to photography, and corresponded to an anthropocentric view of the world, Japanese arts did not privilege human figures but rather their belonging to nature.9 Thus, learners would understand why Mizoguchi’s wide shots are not linked to the American classicism inherited from Griffith but to cultural practices established from their local past.

These differences have important implications for the way cinematic paradigms are traditionally defined in film history surveys. Contemporary film courses should note that the notion of cinematic modernity articulated in the sixties (Peter Wollen, Julia Kristeva, James Peterson) is relative to particular cultural contexts. The French nouvelle vague favored wide shots as a response to its own aesthetic tradition – which, ironically, was to an extent a result of Mizoguchi’s influence.

Nevertheless, the Japanese new wave developed a cinematic modernity in opposite terms: using extreme close ups to breakaway from their own tradition. As a result, this methodology would help students to see that Hani and Nagisha Oshima’s close ups have a transgressive sense, but only when set in the Japanese context. Thus, discussions in the classroom should problematize the Western notion of “modernity” and evaluate to what extent its Japanese transliteration, modanizumu, conceals significant differences. For example, Hani’s long takes seemed to challenge classical continuity rules but only in the Western context, as extensive takes were characteristic of Mizoguchi’s “classical” cinema. As a consequence, new pedagogies should provide tools to help learners understand that if François Truffaut or Jean-Luc Godard’s long takes were disrespectful of the French montage norm; Hani’s long takes were not as irreverent in his film tradition. Children in the Classroom (E o kaku kodomotachi, Susumu Hani, 1956).

The aforementioned examples show that incorporating examples outside Western parameters into film history surveys can be extremely difficult. The Japanese case demonstrates how other film cultures cannot be fully understood with the canons, models and concepts available in the West; and in turn, these cinematic phenomena cannot be explained without taking into account the influences coming from the West. Film studies as an academic discipline needs to be redefined, with comprehensive approaches assessing how western modes of filmmaking were exported worldwide, and the ways in which they triggered an impure cinema interlocked with local aesthetic and philosophical traditions. For this reason, replacing film history surveys with topic courses about the transnational can be a useful way to challenge both the Eurocentric perspective that assumes that the rest of the world merely adapts Western patterns; and Orientalist approaches that only assess the “other” cinema in terms of difference and alienation from the Western norm.

Notes

1. Donald Richie was the first to discuss the Japaneseness of Ozu’s works in Ozu: His Life and Films (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974).

2. Audie Bock proposed an early division of Japanese cinema into three paradigms: Early Masters, Postwar Humanism, and New Wave. (Bock, Audie, Japanese Film Directors. New York: Kodansha International, 1978). However, it was David Desser who used the term “classicism,” renaming Bock’s paradigms as Classical Narrative, Modern Paradigm, and Modernist Paradigm (Desser, David, Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to The Japanese New Wave Cinema. Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1988).

3. For an account on the origins of these theatrical characters see Tadao Satō (Trans. Gregory Barret), “Developments in Period Drama Films,” Currents in Japanese Cinema. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1982, 38-42.

4. For an account on the concept of kire see Ōhashi Ryōsuke, Kire no kōzō. Nihonbi to gendai sekai [Structure of Cut: Japanese Beauty and Contemporary World]. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1986.

5. Burch defined these empty takes as “pillow shots” in To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979). For a formal analysis of this stylistic trait see David Bordwell, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

6. For Oshima Nagisha, Mausumura’s fast montage brought fresh air to Japanese cinema while, in fact, it reproduced a Hollywood-like editing rhythm. See Oshima Nagisha, “Sore wa toppakōka! Nihon eiga no kindaishugishatachi”, Eiga Hihyō, 07-1958 (“Is This a Breakthrough? The Modernists of Japanese Film”, Annette Michelson (ed.), Cinema, Censorship and the State. The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, 1956-1978. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992, 26-35.

7. Kenji Iwamoto, “Japanese Cinema Until 1930: A Consideration of its Formal Aspects”, Iris, nº16, 1993, pp. 9-23.

8. Béla Balázs cited in Kenji Iwamoto,“Japanese Cinema Until 1930: A Consideration of its Formal Aspects,” Iris 16, 1993, 12.

9. Iwamoto, ibid.

Marcos Centeno, PhD, is lecturer in Japanese Studies and Japanese programme director at Birkbeck, University of London, where he teaches Japanese cinema and other modules related to Japanese contemporary culture and society. Before that, Centeno worked for the Department of Japan & Korea at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS); there he convened the MA “Global Cinemas and the Transcultural” for several years, and taught its core course Cinema, Nation, and the Transcultural as well as other Japanese cinema courses. Centeno was also Research Associate at the International Institute for Education and Research in Theatre and Film Arts of Waseda University (Japan) and Research Fellow at the University of Valencia (Spain). At the latter, he taught media courses such as Modes of Representation in Cinema and Film Direction. His main research interest is transculturality and nonfiction in Japanese cinema.

Promise of online teaching for English tutors online

The research contains many case studies that investigate how universities and colleges utilized creative teaching and learning strategies throughout the epidemic, as well as how their students responded. As an example: Using pre- and post-tutoring exams and surveys, the researchers discovered that studying with an English tutor online increased students' performance on standardized examinations … Continue reading