Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Against the Global Right Vol 5 (1)

Ranjani Mazumdar, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Priya Jaikumar, University of Southern California

1. Priya Jaikumar (Cinema Journal): The JNU Teachers Association (JNUTA) and the Students Union (JNUSU) have accused the administration of several illegalities and harassment. What are these accusations and what is the administration’s response? Can you offer a brief time line and your most significant points of contention?

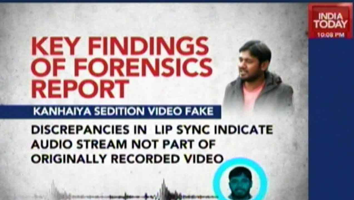

Ranjani Mazumdar: Since February 2016, the students and teachers of India’s premier public institution, Jawaharlal Nehru University, have been at the receiving end of extreme hostility from a puppet administration put in place by the majoritarian Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which came to power in 2014. A few weeks after the University’s new Vice Chancellor Jagadesh Kumar (reported to have links with the Hindu fundamentalist Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh or RSS, the parent organization of the ruling party) took over JNU’s reins, the president of the students union, Kanhayya Kumar, was arrested and charged with sedition for allegedly shouting ‘anti-national’ slogans at an event on Kashmir. This was captured on video. Six other students, also named by the police, were arrested. These events, which occurred on February 12, 2016, led to country wide protests, political debates in parliament and heated discussions on issues related to nationalism, patriotism, the freedom of expression and sedition laws. While the print media was divided, most television channels participated in a systematic targeting of the campus as a den of ‘anti-national’ activity. In the last few years, large sections of the broadcast media, owned by a few conglomerates, have been steadily shifting to the right and virtually act as campaigners for the regime in power. Interestingly, the entire case against the JNU students hinged on a blurred video of the meeting that supposedly contained incriminating evidence about the accused. The media often telecast this video as part of their sensational reporting of the JNU events, until forensic examination brought to light their doctored form. As a conspiracy to orchestrate the entry of administrators sympathetic to the government onto campus became apparent, the Vice Chancellor shifted gears and focused on the University’s internal policies to introduce a relentlessly authoritarian style of governance. The initial hysteria against JNU was the prelude to creating an atmosphere conducive to this assault.

In JNU’s almost fifty-year history, its teaching community has played an important role in governance, and the ordinances of the institution reflect the operative norms of such a participatory model. For example, the appointment of Deans and Chairpersons of Schools and Centres, respectively, was based on a non-discretionary rotation system. Most teachers have been members of the Academic Council (AC) at some point in their tenure. Academic and administrative matters are usually debated at the level of the Schools and Centres before they are taken to the AC for discussion, final approval or rejection. Although the Executive Council (where AC decisions are ratified) has always had several government-appointment members, rarely in the past have such appointees been of a specific ideological persuasion or political affiliation. Under Jagadesh Kumar, the AC today has become a farce. It operates like a mafia like set-up where the Vice Chancellor reads through and approves the minutes of the previous meeting. Policy decisions are announced on the basis of false and manipulated minutes, with no discussion. Through such blatant abuse of the AC, the Vice Chancellor has made drastic changes to the statutes and ordinances of the University. The Executive Council is now packed with government nominees.

The Vice Chancellor and the Executive Council have systematically centralized all decision-making processes. The appointment of unqualified faculty close to the political ideology of the government, the abandonment of a constitutionally mandated social justice framework that ensured diversity in student intake, the continuous harassment of the university community through threatening circulars in the name of ‘order and discipline,’ and the constant threat of disciplinary action against JNU students and teachers, have forced many to legally challenge the Vice Chancellor’s actions. Several cases are now pending in the High Court and are embroiled in the red tape of judicial time. The message is clear: Destroy India’s highest ranked University, known for the quality of its academic output, its commitment to social causes and its vibrant culture of dissent and debate.

2. Priya Jaikumar (Cinema Journal): Have you been able to teach any classes over the past year, and particularly the past few months? Do you think the ways in which you teach cinema and media classes will change after this? Does this transform your understanding of how cinema and media should be taught?

Ranjani Mazumdar: Yes, we have been able to teach despite all the crisis because both students and teachers are committed to pedagogy and learning. It has been difficult since political turbulence on campus does affect our day to day functioning, but we are working collectively to create a situation where our teaching continues. Notably, our challenges and responses have had a particular relevance to the field of Cinema and Media Studies, which is located in JNU’s School of Arts and Aesthetics (SAA) along with Visual Studies and Theatre and Performance Studies. Our Theatre and Performance students have staged powerful plays against the administration. The Visual Studies students have collaboratively used popular poster art for public campaigns. The Cinema Studies stream invited actress Swara Bhaskar with her Anaarkali of Aarah, about a feminist crusade for justice against a corrupt Vice Chancellor. At the end of a three-day hunger strike by JNU teachers, our School faculty initiated a flash mob at the entrance of the University that became viral within minutes of the action. Students participating in a lockdown to protest high handed University actions created a novel form of the video parcha (video pamphlet) to keep the public informed of the issues on campus. Our effort through all these interventions has been to broaden the language of protest to introduce new forms of civil disobedience.

Most recently, the Vice Chancellor introduced a mandatory attendance system and dismissed the SAA Dean, Kavita Singh, along with seven other Chairs, for not complying with the policy. They have been reinstated following an order of the High Court until the final outcome on a petition filed by the dismissed Dean and Chairs. Many teachers have written articles in the press to explain why mandatory attendance is counterproductive in an institution where various kinds of assignments have been evolved to ensure student participation. This is especially important for a research institution where graduate students are supposed to spend the bulk of their time in archives, doing fieldwork and working in libraries. The University has demanded that even after course work is over, students must report every day to sign a register before they go about their work for the day! The issue is not attendance but the instilling of a culture of fear and constant threat of expulsion, which is demoralizing students and faculty.

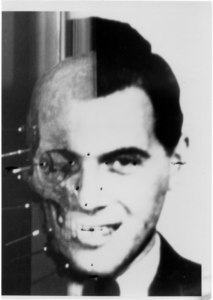

For cinema and media scholars, another major issue is the role that doctored videos and fake news items about JNU played in churning out gross falsifications in the media. The semester after the arrests of the JNU students, I taught my regular M.A course on Film/Media Theory and Aesthetics, which introduces students to the theoretical debates governing the ontological status of cinema, its relationship to other media forms and its transformed nature in the digital age. The last session is dedicated to an exploration of forensics as an aesthetic form that has in the recent past become all pervasive in television crime shows and cinema. For this session we read Eyal Weizman and Tom Keenan’s well-known monograph Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of Forensic Aesthetics. The authors in this book track a key event of the mid 1980s when the body of Joseph Mengele, the Nazi doctor responsible for some of the worst human experiments at Auschwitz, was exhumed from his grave in Brazil. Forensic experts were put to task to gather details such as dental records, photographs, medical papers, prescriptions etc. What followed was a trial of the bones and video images of Mengele’s photographs, which were merged with the skull via an elaborate two camera set-up, one focusing on the photos and the other on the skull. The recordings were fed directly into an image processor and the layered output was displayed on a monitor. A press conference for the world media displayed the elaborate layering of the skull with Mengele’s photographs, creating a ghostly combination that exuded tremendous performative power. Inanimate objects (in this case bones) emerged as agents in the legal and public domain, triggering a new forensic imagination. While forensic experts felt confident of the results, they acknowledged there would always be a margin of error. Forensics as Weizman and Keenan argue is an imagistic performance of truth that requires an object, a mediator and a forum, all of which was mobilized for the staging of Mengele’s skull. This case established forensic identification as a field and took it beyond courts and tribunals into the realm of public media discourse and popular culture.

I extended this discussion of forensic aesthetics to a discussion of the blurred video of the JNU students in class. While the videos were doctored, the staging of a ‘truth discourse’ was conducted through a marshalling of forensic information by television anchors. A different soundtrack was added to give a communal twist to the slogans. Even if the labs came back later to say the videos were doctored, the damage was done through an involved performance of the forensic imagination with the video as the object, the TV anchors as the mediators, and the public as the forum. It became increasingly clear that we need to pay careful attention to the elaborate ways in which ‘facts’ are made to circulate in our contemporary digital landscape. This was a moment that brought all the debates of our course to a close, and the role of aesthetics as a public discourse became sharply clear for me.

As we move on further into a digital future, the density of the landscape we live in gets more complex. The constant circulation of fake news, false tweets, photographic fallacies, doctored evidence and trolling has made me acutely aware of the need to encounter this contemporary new media landscape. We need active research and intervention into the dense configuration of our contemporary digital world. It is time to close in on this moment to recognize it not just for what it can tell us about cinema’s genealogy or ontology, but for the way it is reframing ideas about life, history, politics and evidence.

3. Priya Jaikumar (Cinema Journal): Based on your experiences over the past year, is there anything you would want to tell the broader global educational community that is involved in teaching film and media, and what do you seek in terms of acts of solidarity?

Ranjani Mazumdar: The battle with the JNU Administration has been exhausting and has affected all our academic pursuits. Resistance for us is not a diversion or option, but an absolute necessity. While most students and teachers are genuinely interested in research, the future is uncertain as financial support is withdrawn on a regular basis. We hope the global educational community can reflect on this and look for ways to support collaborative research ventures. It would also help to fight the online propaganda with counter tweets and statements sent directly to the Vice Chancellor and the Prime Minister of India!

Relevant articles to read with this interview

- https://thewire.in/education/jnu-school-of-arts-and-aesthetics

- https://thewire.in/education/jnu-administration-jagadesh-kumar

- https://scroll.in/article/868724/it-is-illegal-jnu-has-made-marking-attendance-mandatory-heres-why-we-are-refusing-to-do-so

- https://thewire.in/education/jnu-hiring-attendance-students-admission

- https://www.dailyo.in/politics/jnu-vice-chancellor-m-jagadesh-kumar-selection-committee/story/1/21571.html

- https://www.dailyo.in/variety/jnu-jagadesh-kumar-jawaharlal-nehru-university-higher-education-nationalism/story/1/23142.html

- http://thecriticalmirror.com/analysis/unraveling-jnu-crisis-conspiracy-suppression-democratic-voices/2017/07/31/

Ranjani Mazumdar is Professor of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) where she offers several graduate courses on the history, theory and aesthetics of the moving image. In her seminar on “Cinema and the City,” she locates cinema as an innovative and powerful archive of urban life. Her course on “Film and the Historical Imagination” makes connections between history and evidence, and historical memory and representation. “Film/Media Theory and Aesthetics” explores the ontological status of cinema, its relationship to other media forms and its transformed nature in the digital age. A required seminar on “Research Methodology” explores the context of media via histories of technology, perception, production, circulation and consumption. “Critical Theory to Cultural Studies” is taught as a seminar to introduce conceptual debates on the complex status of culture in industrial and post-industrial societies. A course titled “Indian Cinema: Past and Present” is taught every year to provide a background to the landscape of Indian cinema as well as trace the specific genres, thematic concerns and formal makeup of popular cinema.

Priya Jaikumar is Associate Professor at the Division of Cinema and Media Studies in the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. At the University of Southern California, she teaches graduate seminars and undergraduate courses on topics in international cinema, film aesthetics, genre studies, critical space studies, anticolonial and postcolonial theory, cinema and modernism, Indian cinema, and other national cinemas. Her thoughts on teaching anticolonialism and postcolonialism in a film studies course appeared in Postcolonial Cinema Studies (Routledge University Press, 2011), in conversation with the anthology’s co-editor Sandra Ponzanesi.