Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Vol 4 (1)

Kimberly Katz, Towson University

Laila Shereen Sakr, University of California Santa Barbara

In 2011, when the uprisings broke out, many of us became glued to the news and grew hopeful for change in the political structure and leadership of Middle Eastern states whose citizens had stood up and protested against long-standing dictators. In the midst of these tumultuous events, the opportunity for new courses emerged across disciplines and sub- disciplines – in Media Studies, History, Political Science, Middle East Studies, civic media, social movements, and many more. Katz knew of the media analytics system Sakr was developing and saw the potential to collaborate using social media in the classroom. Sakr created the R-Shief media system (r-shief.org) in 2009 to attend to critical gaps in computational and textual analysis on social media. R-Shief is an archival and visualizing media system with a five-year archive of over twenty-six billion social media posts (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and sites) in more than seventy languages. Scholars and practitioners from social sciences, humanities, and engineering use R-Shief to conduct computational and textual analysis. R-Shief is not a tool; it is a platform for addressing relevant political and cultural questions. This digital humanities project provides insights into big questions such as: privacy security for individuals; the impact of digital communication as a human right, while investigating how this right is (often) violated or abridge in different geo-political context, and; the structure and practices of the security state. It is an archival and visualizing media system that has played a pivotal role in knowledge production on global social movements over the past six years, most notably the 2011 Arab Uprisings and Occupy Wall Street movements.

From 2011 through 2016, Katz and Sakr continue to collaborate on lesson plans to include social media analysis on the Middle East in Professor Katz’s Freshman Seminar at Towson University. In this paper, we document the lesson plans and the changes made in the course highlighting Spring 2014 and Fall 2015 semesters. We also track successes and failures and pedagogical changes to improve student success in the classroom. We assess the various technologies used, existing barriers, and how social media analytic tools have offered students new learning environments. Through a critique of database narrative and social media infrastructure, we articulate techniques of information analysis as a research method in the humanities.

At Towson University, Katz developed a Freshman seminar that falls under the Core Curriculum. The Towson Seminar (TSEM) is designed to teach all incoming students common research and writing skills necessary to produce a semester-long research paper. The background of the students is mixed on every level. Students do not yet know their major, particularly if they are first semester freshmen; they come from all parts of Maryland and the Mid-Atlantic region, and beyond. They are ethnically and religiously diverse. Their international experience coming into Towson University is also mixed.

In the two TSEM sections that incorporated research from R-Shief, from which Katz drew data, the interest level of many students increased as they began to understand something about the topic. However, many students found their overall research papers quite challenging. The university keeps enrollment at approximately twenty students so the course can be run as a seminar. Formal lectures were not offered, but Katz often expounded on the material, as the students did not have the requisite background on their country of study. To rectify that in the following semester of the collaboration, Katz added a historical background assignment at the outset. Students’ work across the semester focused on the unfolding of the Arab uprisings, from country-to-country, as well as the situation in neighboring countries, such as Saudi Arabia, where uprisings were prevented.

The purpose of this collaboration between Katz and Sakr was to incorporate digital research methods in an assignment that explored social media stemming from the uprisings. We wanted students to think critically about how to use social media, in political protests and activism, and more seriously, in the very dangerous work of toppling dictators that can result in state-sanctioned beatings, torture, and the imprisonment of protestors. As a historian, Katz wanted them to think about social media as a non-conventional primary source for writing an academic paper. For Sakr, this collaboration became part of a project to develop a teaching module for using social media to help others understand some of the complexities of the Arab World through a set of methodologies that emerge at the intersection of both cultural and media analytics.

Katz’s students worked with Twitter as their social media platform and they relied on R-Shief to search for historical tweets from the period of 2010-2013, which coincided with the period of the onset and first few years of the Arab Uprisings. Students were able to search R-Shief’s voluminous archive for hashtags and then plot the hashtag within a specific date range into R-Shief’s Visualizer, which gives them a method for analysis as it plots tweets on a graph over a period of time. If they had been doing their research thoroughly, they would likely know when there would be interesting dates to select for their country. If not, however, how would the results be meaningful by selecting random dates? The exercise came first and once they had mastered the exercise and written a short paper, they could go back to R-Shief for the longer paper that they were to produce after a semester’s worth of research.

To introduce the assignment, Sakr gave a Skype presentation on two points: how to navigate the interfaces of R-Shief, and conceptually about the hashtag (#). The hashtag discussion raised great interest; while most of them knew about hashtags, having read or even created them, they had never really thought about the word selection for a hashtag. Sakr gave a careful explanation about the choice of words for hashtags, noting that they carried political resonance. Why a tweeter chooses #Syria or #Bashar may mean that she is either for or against the government or the embattled president. By tweeting the hashtag #OccupyDamascus, for example, people aligned themselves in global solidarity across the Occupy movement, which gained some traction in 2011 in cities across the globe on the basis of economic and political inequality.

Some students, in contrast to the assignment’s objectives, searched for individual tweets outside of R-Shief, which they then attempted to analyze without any frame of reference. For example, one student studying the Egyptian uprising found a random tweet by @youben12 commenting that the servers in Egypt were unavailable and possibly blocked in Egypt. The student found the tweet by searching through Twitter filtering through both hashtags #Jan25 and #Mubarak. He concluded that the Egyptian government was trying to disrupt communication in Egypt by shutting down the Internet. He was not wrong in the conclusion, as the Egyptian government had, in fact, shut down communications for a period of time, but @youben12 (an unidentifiable user) would not have been able to send his tweet had he been in Egypt. The student’s methodology was flawed even if his conclusion was correct.

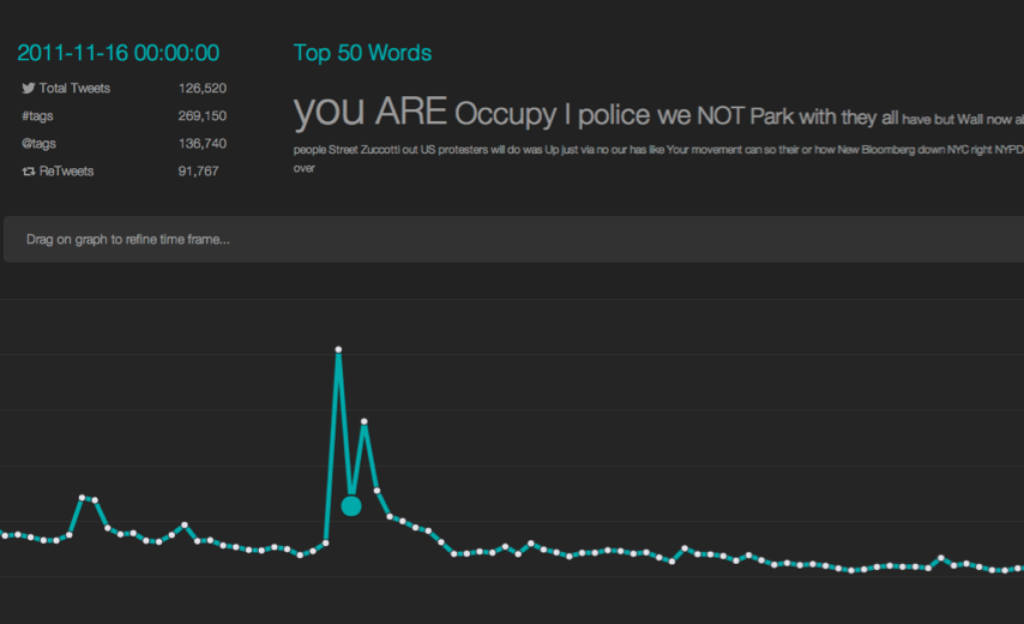

Figure 1. The Visualizer plots the tweets across a specific period of time and notes the spikes in dates when the number of tweets was particularly high based on the search term, i.e. the hashtag that the students had input in their initial search that led them to the graph on the Visualizer.

Figure 1. The Visualizer plots the tweets across a specific period of time and notes the spikes in dates when the number of tweets was particularly high based on the search term, i.e. the hashtag that the students had input in their initial search that led them to the graph on the Visualizer.

For the students who did grasp how to use the R-Shief platform, they realized that they had a range of search capabilities to use. By inputting search terms and dates, one can sort the results by language, by date, and by the highest frequency tweeter. These students also realized that the Visualizer plots a timeline of the uprising set against the meaning of the hashtags. The top fifty words appear at the top of the graph with the dates at the bottom of the graph.

While some students wrote about tweets and social media as an inevitable part of the modern world, they found a number of problems in trying to determine the value of the tweets for academic writing. They realized that they could not access most conversations without knowledge of Arabic; they had to focus on the English-language tweets only. Indeed, that has long been a problem of the field and scholars, who try to conduct research without knowing the requisite languages, or instead do so by relying on translators. At the level of undergraduates, it is understandable that most do not know the languages as they try to gain an understanding of this complex region. In fact, they are already highly cognizant of the significance of being able to access the language of a region and its people, in this case, Arabic. They do not see that it should be dismissed or always translated rather than understood in its original diction.

Students raised concern and saw value in the tweets as a primary source for academic writing. They had difficulty in determining a tweet’s “reliability.” For example, some students saw them as the “real beliefs of the people uncensored,” or “people passing on a message or image from the war,” or, with regard to the pro-Assad tweets, “a first- hand way of understanding how the unpopular side of the war feels.” They also saw the value of the velocity of generative social media posts, in contrast to traditional sources such as surveys or interviews. No student raised problems with other kinds of sources, such as official records, government documents, etc., making one consider that the newness of tweets as a research tool for students, especially freshmen, is rather jarring.

It is curious to think of where we are going and to identify emerging alternative narratives. We are already seeing a shift from when we began tracking students in this project — the early adopters of social media are no longer tweeting. By 2016, we find that security state and corporate interests have diluted the narrative on platforms like Twitter and Facebook. And current social media analysis requires another set of considerations about users and the networked or growing un-networked sphere. Five years after the first classroom collaborations, we can gain some insight about the significance of social media platforms to understanding the Arab Uprisings and Occupy movements. Students study the social movements while participants take to the streets. These platforms and classroom activities play an important role in the ongoing battle over the narrative of those years. Through the R-Shief archive, students today can take a long view over the past five years and make visible the shifting network and its assemblages.

Kimberly Katz is Associate Professor of Middle East History at Towson University in Maryland. She holds a Ph.D. in History and Middle Eastern Studies from New York University and is the author two books: Jordanian Jerusalem: Holy Places and National Spaces (University Press of Florida, 2005) and A Young Palestinian’s Diary: The Life of Sami ‘Amr (University of Texas Press, 2009).

Laila Shereen Sakr is Assistant Professor of Film and Media Studies at UC Santa Barbara. She has been an online tutor at the Teaching Media Community for 5 years. She is known for creating and performing the cyborg, VJ Um Amel, and the R-Shief media system. She holds a Ph.D. in Media Arts + Practice from the University of Southern California, an M.F.A. in Digital Arts and New Media from UCSC, and an M.A. in Arab Studies from Georgetown University.